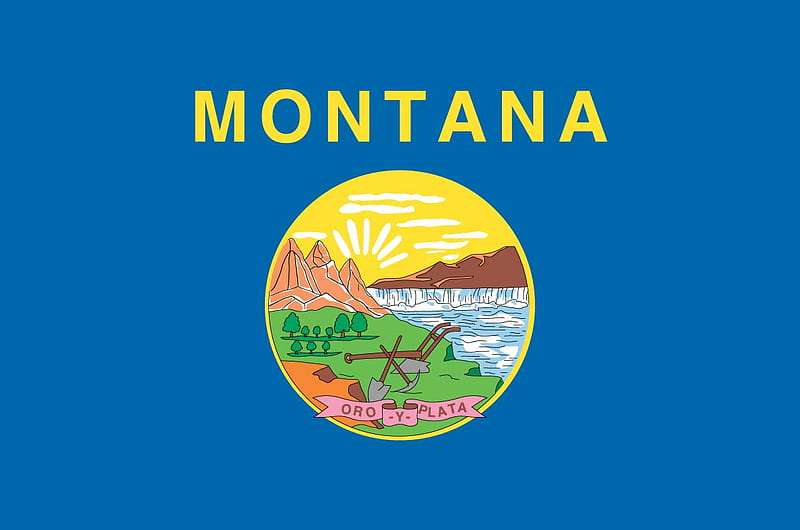

Montana did not have a state flag in 1898. The Great Seal of the State of Montana is illustrated on a rectangular banner, which the Ninth Legislative Assembly of Montana agreed to designate as the official Montana flag in 1905. Some states have held competitions to choose the best design for their official state flag. Colonel Kessler, head of the First Montana Infantry, took the initiative that gave birth to the state’s design.

The First Montana Infantry, made up of volunteers from various Montana towns, trained at Fort William Henry Harrison in the spring of 1898 in preparation for the war with Spain. These volunteers were “whipped” into fighting shape by Colonel Kessler. These men were given a 45-star American flag by the Helena women to serve as their Regimental Colors throughout the battle.

Colonel Kessler, working alone, commissioned a distinctive flag for the First Montana Infantry because he believed that his unit of combat volunteers needed a distinctive flag or banner to set them apart from other forces. The built Montana flag included an embroidered rendition of the Montana state seal over a dark background. Above the state seal, this handmade silk flag read “1st Montana Infantry U.S.V.”

The First Montana Infantry took this flag with them when they went to battle in the fall of 1898, and it served them well. A year later, when the First Montana Infantry volunteers came home, Colonel Kessler’s Montana flag had risen to prominence and, despite not being an official state flag, was seen as a suitable representation of the state. Colonel Kessler presented the flag to the governor in Helena, where it was made available for display all over the state.

Many people believed that the regimental flag of the First Montana Infantry should be honored with official recognition as Montana still struggled to find an official state flag. Colonel Kessler’s flag was declared the state flag of Montana by the Ninth Legislative Assembly in 1905. Naturally, the phrase “1st Montana Infantry” was removed.

The flag has undergone two modifications since 1905. The legislature approved a bill in 1981 mandating the placement of the phrase “MONTANA” above the seal in Roman characters. This was done so that, from a distance, the Montana flag could be distinguished from those of other states.

Jim Waltermire, the secretary of state, also specified the colors for the state seal on the flag, which ranged from a gold sky with white clouds and sunrays to blue and white waterfalls. In 1985 the letters that make up the word “MONTANA” were given a more precise definition. To avoid the vast range of styles used by flag producers, “helvetica bold” was specified.

Montana flag consists of a dark blue field with the dimensions of 2:3 of length to breadth. The blue color signifies its inclusion in the Union of States and the name of the state, Montana, lies painted in yellow above the state seal.

The State seal includes a representation of the Rocky Mountains illuminated with shafts of the Sun. These mountains are essential to Montana’s topography and to its name, because the name Montana is a derivation of the Latin montana which means ‘mountainous’. The seal also depicts the Missouri river and forests, referencing Montana’s vast swathes of natural bounty and its preeminence in forestry and agriculture. Pivotal to the design is the Great Falls, a memorable landmark that has become a favourite among tourists. The plough and crossed pick and shovel symbolise agriculture and the mining industry, the main drivers behind the economic potential of the state around the time of the design of the seal. This spirit is reflected in the state motto, written in Spanish, “Oro y plata” (“Gold and silver”), which manifests itself on a ribbon in the seal.

We may now attempt to focus on how the topographical inheritance of Montana and its natural resources paved the way for it to be one of the powerhouses in mining and agriculture. This might afford us fresh insights into the cultural capital of these elements for them to make their way into and maintain their relevance to the state seal.

Heritage of mining in Montana

Mining exercised an important role in Montana’s growth from wilderness to bustling civilised place. The pioneering miners were men hunting for fortune, who dared into rich areas and quickly left behind barren sites. These miners made use of mining methods that used water and necessitated simple equipments such as a gold pan, pick, shovel, and a water source – giving us a context for including the images of the crossed picks and the shovel in the state seal.

Montana had three major incidents that produced large amounts of gold. In July 1862, a prospector named John White and his partner discovered gold at Grasshopper Creek and built the town of Bannack around the momentous location and it generated a whopping five million dollars in gold dust in the first year.

In 1863, two men left Bannack in pursuit for gold, bringing them at loggerheads with the Crow Indians who snatched the miners’ equipment and ousted them. On the return, they camped along Alder Creek and decided to pan for a while. Their act of panning yielded gold and within a few months teeming masses of people had migrated to the area around Virginia City.

In 1864, a group hailed as the Four Georgians began working their labor at Last Chance Gulch. In the course of the next four years, Last Chance Gulch fetched nineteen million dollars in gold and soon the city of Helena emerged around it . Some time after this, Sidney Elegerton successfully managed president Lincoln to cut up the area which led to the structure of Montana as we know it today and it was given the celebrated nickname of ‘The Treasure State’.

Mining in Modern Montana

Mining in its full activity is conducted in 29 of Montana’s counties and a total of 26 minerals are mined. The Industry research firm IBISWorld claimed that in 2018, the sum total of Gross Domestic Product accrued by mining in Montana totaled 2 billion Dollars and employed over 12,000 residents of the state and establishing beyond reasonable doubt the continued importance of mining in the economic affairs of the state.

Agriculture in Montana

Montana is the place where rivers and streams separate at Triple Divide Peak into three distinct streams toward Hudson Bay, Atlantic Ocean or Pacific Ocean. It possesses a fertile environment that has effected a powerful agricultural economy.

In the course of history, regional marketing venues such as Billings, Glasgow, Havre shaped up as railroad hubs where farmers could sell their grain and cattle and come to purchase supplies.

Agriculture forms the state’s largest industry. The state sports approximately 28,000 farms and ranches sprinkled across an area of 59.7 million acres, averaging a mammoth 2,134 acres each. Generating a wide range of commodities, wheat and beef are Montana’s top offerings.

Montana leads the nation in the production of certified organic wheat, dry peas, lentils and flax, and ranks second in the country for its honey and pollination industry. Altogether, the overall agricultural output brings an average of $5.2 billion to the economy on an annual basis. Thus we have most of the major outlines of the historical and continued relevance of agriculture in the substance of the culture and the plough in the symbolism of the seal does justice to the force of this reality.

History of the Seal

Long back in 1865 when Montana was a territory and not a state, a legislative committee headed by Francis M. Thompson tried to create a state seal. Apart from a shovel, a pick, and a plough to capture the economic promise, they additionally envisioned mountains, trees, buffalo, and other animals and settled on a territorial motto of “Gold and Silver”. But with the passing of the legislation, and as various designers and artisans became stakeholders in the process, queer things started to happen to the design of the seal. The motto was shabbily mistranslated at one instance, and was righted from “Oro el Plata” to “Oro y Plata”. The abundance of animals that were originally legislated diminished to one solitary buffalo. At another juncture , in 1876, the buffalo vanished from the seal totally. In the year 1887, mountains changed contour, the skies lost their clouds, trees multiplied, and even the alignment of the sun underwent change.

When Montana attained statehood in 1889, the design was argued again. In 1891, the addition of 41 stars was proposed to signify the states, and the addition of new symbols were proposed some of which include Indians, buffalo, settlers and their wagons, a train, a stage coach, horses, sheep, cattle etc. Amidst this bedlam of symbol frenzy, the legislation failed and it was agreed that a better remedy would be to employ the existing territorial seal, and modify the word “Territory” to “State”.

Lastly the engraver, G.R. Metten, commissioned to produce the seal, took it as his task to reverse the flow of Great Falls and the Missouri River, relocate some trees, and redraw mountains. The Third Legislative Assembly afforded sanction to the Territorial Seal as The Great Seal of the State of Montana. The resolution which thus constituted the new adoption was passed on March 2, 1893.

Observations

The potency of the symbolism of the Montana flag hasn’t quite managed to hold its sway over the people of the state. The odds of a Montana knowing the answer to that question is low.

In fact, a University of Montana poll found only 30 percent of registered voters surveyed successfully answered what the state motto was. This phenomenon of some of Montana’s traditions faltering spurred a North American Vexillological Association survey that ranked Montana’s flag 49th for its aesthetic and cultural appeal.

About Montana

Despite being one of the least densely populated states in the union, Montana is the fourth-largest state in terms of area in the United States, after Alaska, Texas, and California. The National Hub for Frontier Communities used a matrix that takes into account population density as well as the distance and travel time to a service/market centre to identify 50 of Montana’s 56 counties as “frontier counties” in 2000. In 2010, there were 6.8 people per square mile in Montana.

Despite having a name derived from the Spanish montaña which means “mountain” or “mountainous region,” Montana has the lowest average elevation of the Rocky Mountain states at only 3,400 feet. The Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, located in Montana, commemorates the famous conflict between the Sioux tribe and the American Army in 1876, often known as “Custer’s Last Stand.” The country’s first national park was created in Yellowstone National Park, which is situated in southern Montana and northern Wyoming.

In 1932, Glacier National Park in Montana and Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta, Canada, were united to create the first International Peace Park. Because of the two parks’ abundant and diversified plant and animal life as well as their breathtaking scenery, UNESCO designated them as a combined World Heritage Site in 1995.

Flathead Lake is the largest freshwater lake between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Ocean, having been carved by glaciers more than 10,000 years ago. It spans an approximately 200 square mile area and is 28 miles long by 5 to 15 miles wide.

By: Srijani Das